My son has finally found his confidence as a reader. He’s comfortable in so many other aspects of childhood. He can handle himself on the pitcher’s mound, for instance, staring down a batter while facing a full count with the game on the line. He’ll slurp a plateful of oysters or any other unusual food we put in front of him, without hesitation. He’s sure of himself socially, able to hang with adults or kids of all ages. But when it came to reading, he’d been full of frustration and defeat, giving up at the first moment of struggle. Then over the past couple months, he discovered a book series he loves, and my wife gently and consistently encouraged him, and now he begs to read to us each morning. I hope it lasts.

My wife and I are book lovers and collectors, so our son’s resistance had been particularly dispiriting. We have a house filled with books, lining the walls, taking up space, reminding us of their presence each time we pass through a room. We want our kids to love reading as much as we do, and we’re still in that golden moment in which our children shape themselves in our image, but that won’t last long. Soon our kids will push away anything we slide in front of them, and so persuasion may not be the best approach. Every parent knows that for your kid to truly want something, that thing needs to be against the rules and off-limits.

Many years ago, I traveled to Santa Barbara to interview the writer Thom Steinbeck, eldest son of the great author, for a documentary I was producing about The Grapes of Wrath. Thom gave a generous and intimate interview, sharing personal stories about his dad alongside shrewd literary insights.

I didn’t yet have kids of my own, but Thom told a story that day that has stuck with me, and I promised myself I would steal this trick if I ever became a father. My kids are still a bit young for it, but someday I’ll do it.

Here’s Thom telling the story in all his raspy charm, followed by the transcript, if you’d prefer to read it (slightly edited for clarity).

[My father] actually once bought this lowboy cabinet and locked all the books he wanted us to read in it with this gigantic key and hid it on top. We went through that in about two years. We’d sneak down every night with flashlights and unlock this thing. We were about eight and nine. And my father said, “Don’t ever let me catch you touching anything in that cabinet.”

Every night he'd make a big deal of it. It had a door on it with this massive brass lock and a key. And there were chairs on either side of this big chest, and it had grates on the front of it. It looked like a priory door, you know, it looked like a prison.

And there was, you know, Twain and Coleridge; I mean, everybody was in there that he thought that everybody should read, that young people should read.

Every night he'd lock this thing, and it made an incredible noise. And he'd stand on the chair, and he was tall, and he'd put the key on top, making sure that we saw that.

I should have caught on. We were being had. We were just being totally had.

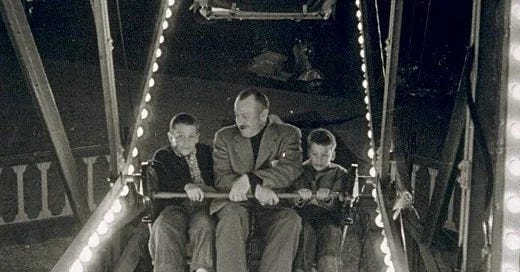

So my brother and I would sneak down the squeaky stairs. We lived on the fourth floor; his bedroom was on the third; and the second floor was the library, the library and the living room. And between the two—it was a brownstone in New York City—was this gigantic chest. We’d sneak down with our pillows, and I’d get my brother on my shoulders, he'd get the key, and I'd come sneak down and put the pillow over the lock, so you could take it out, got our flashlights going.

Because my father said there was a secret in there that we weren't supposed to know. That was the other sucker trick: He said several of the books in there have got secrets that I don't think that you should know. That just hammered down the lid, as far as I was concerned.

We did this for months. And I was always amazed that my father always made sure there were plenty of batteries in the house, and I could never figure out that one. Those old D batteries and D flashlights, and my Boy Scout flashlight, olive drab, with a clipped-head flashlight. I was trying to figure out what the secret was, and reading these things.

And since my father knew where every book was, we would have to sneak down the same night and put them back. So we got very little sleep for the longest period of time.

Years later, I'm sitting at a dinner party—my father gave a dinner party—and the conversation came around, we were just talking about really esoteric people out there, esoteric writers that no one ever reads anymore but that had a lot of impact. And this conversation came up about Farquhar who was a humorist, an English humorist of, I think, the 14th century—I don’t know; I've forgotten now. At any rate, I sort of put in my two cents about Farquhar.

My father looked at me, and he said, “What do you know about Farquhar? They don't teach Farquhar in school.”

I said, “Oh, I remember there was a book around here.”

My father knew exactly where the book was. He'd locked it up, right? And he gave me this look, and suddenly I found I'd been caught in the middle of something because I suddenly remembered where I'd gotten the book of Farquhar. It was in this cabinet.

And my father looked over at me, and like this inside joke—there were eight other people at the table—he said, “You know, son, if you'd oiled that lock on that damn door, a lot of us would have gotten a lot more sleep.”

This was a treasure! Thank you !

- from a fellow house lined with books

That is delightful!

What I love most about that is that, in one way, Steinbeck was playing the long game, knowing that one day his kids would be adults, and he could bring that cabinet up and just give them a sly wink, and the 15, 20-year-set up would pay off in that shared joke when his sons remembered the cabinet and realise they'd been had.