Years back I ran a magazine called Radio Silence with a handful of friends. The focus was literature and rock & roll, and we invited writers and musicians to contribute. A highlight of those years was flying to LA with our contributing editor, Ben Hedin, to interview Lucinda Williams in her home at the edge of the San Fernando Valley. Her dad, Miller Williams, had long been one of my favorite poets, and of course I loved Lucinda’s music.

Ben was pals with Lucinda and her husband/manager Tom Overby, so really all the credit for this goes to Ben. He’s a terrific interviewer and writer, and I basically sat there holding the mic, soaking up the amazing stories Lucinda told about her father and her path to becoming an artist, and draining glass after glass of wine as we worked our way through most of a case, very late at night.

Lucinda was disarmingly intimate and vulnerable, crying when the emotions tipped over the edge and sometimes getting up from her place at the table to hug each of us before sitting back down to continue.

While Lucinda really did chase Flannery O’Connor’s peacocks when she was a child, that’s not really what the conversation was about. (Yet what a gorgeous metaphor for a budding artist; I still feel like I’m always just chasing Flannery’s peacocks every time I sit down at the desk.)

This piece is essentially about artistic inheritance—what we glean from our elders, what we pass down to our kids, how Lucinda’s father both protected and encouraged her as she pursued a creative life.

In Radio Silence, we ran the piece as a sort of memoir, straight from Lucinda’s mouth to the page. Below is the result.

-DS

My dad, when he was a younger writer, always had a mentor. Flannery O’Connor was one. We lived in Macon, Georgia, and she was in Milledgeville. So my dad took me. And this is what’s so beautiful about the story: O’Connor—unlike me—was very disciplined. She had a certain time that she would write. She would get up at eight in the morning and write till three in the afternoon, and if the shades were down, that meant she was writing and you couldn’t come in. We showed up, well, she was still writing, so we had to sit out on the front porch until she was done. And she raised peacocks; my memory is of chasing her peacocks around the yard.

When I was about fifteen and sixteen I discovered her writing and read everything I could get my hands on, which wasn’t that much. But I read everything, and I also devoured Eudora Welty’s stuff. But for me, Flannery O’Connor was to writing what Robert Johnson was to blues. That might be the best way to say it. There was something about her stuff that was just a little more crooked, a little more weird, a little more out there. My song “Get Right With God” and my song “Atonement,” I got a lot from her novel Wise Blood. I was sleeping on a bed of nails. Wise Blood is about this guy who befriends this preacher who pretends to be blind. He’s a total con man, and this kid befriends him. At the end, the kid decides he’s got to be like Jesus Christ and suffer. He fits this barbed wire on his bed.

I have fond memories of the sound of my dad’s typewriter, which you don’t really hear anymore. I always knew when my dad was on the typewriter, something good was going on. As soon as I could read and write, I started writing little poems and short stories. I was six years old. I was always one of those kids who could entertain myself for hours sitting and writing or drawing.

I don’t know if it happened that I became a writer because I wanted to please my dad, or if it just came naturally to me. Maybe it was a combination. I just remember enjoying creating—writing and creating—from a young age, and eventually that spilled over into music and wanting to learn some kind of instrument. My mother is a musician, and there was always a piano in the house. Probably most of it was genetic, or part of it was genetic. We don’t really know why we’re drawn to certain things, you know?

I had all these heroes when I started out, like Joan Baez and Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, all these traditional folk singers. And later Judy Collins and Bob Dylan. Highway 61 Revisited was the first Bob Dylan album I heard. A student of my dad’s came over to the house one day with a copy of that album, just raving about it, and I put it on the turntable and started listening. I was only twelve, so I didn’t understand everything on it, but I went, wow, this is a culmination of the two different worlds that I’ve come out of, the literary world and the traditional folk-music world. I just fell in love, then and there; I fell in love with Bob Dylan. There was some part of my twelve-and-a-half year-old brain that went: This is what I want to do.

In college—my dad wanted me to get a degree so I would have something to fall back on—when they asked me to put down what I was going to major in, I put cultural anthropology. I didn’t put music. I wasn’t interested in studying music formally. And then my parents split up. My mom was still living in New Orleans and it was the summer, and I went to stay with her, and I ended up getting this job on Bourbon Street at a little folk club. Smack in the middle of Bourbon Street. At the time it was a big deal. It was just for tips, but you could do pretty well back then in tips. And I remember calling my dad and I said, “Instead of going back to school, I want to stay here and do this.” And he said okay. To me, I felt like that was the turning point, because I wanted to please my dad. I didn’t want to disappoint him. I don’t know what would have happened if he had said, “No, I want you to come back.” But because he had been a struggling young poet, he understood the need to follow that path, so he supported me.

During the seventies, I was hanging around Houston and Austin, Texas, playing gigs in clubs. It was a different time than it is now. I wasn’t like, “Oh my god, I’ve got to get a record deal.” I didn’t know anything about the music business. It was just me and my guitar, playing in clubs. There was no music business mentality. I think that proved to be a good thing. Some people might go, “Well, you could have made it sooner,” but I had this group of other musicians, like a support group, and no one was thinking about record deals or the music business. We were just writing songs.

I went out to L.A. at the urging of a friend, late 1984. He said, “Come out and I can get you some gigs.” And I remember when I left Austin everybody said, “Oh, they’ll eat you alive out there. You’ll come back to Texas with your tail between your legs.” And I said, “We’ll see.”

I came out here with this guy I was living with at the time, and in the back of my mind, I think I knew I was going to stay. I wasn’t going back. We ended up breaking up, and I found this place in Silver Lake for like four hundred bucks a month. Cute little duplex. I started playing, and eventually this guy who was the head of A&R for the West Coast for Sony said, “I want to try to convince everybody else at the label.” They gave me what they used to call a development deal. They would give you enough money to live on for six months, and you would write songs, and then the label would listen to it and decide if they wanted to sign you or not.

Well, I’m in seventh heaven at this point. I don’t have to work a day job. I was free to sit and write. I did a demo tape, and they passed on it. Sony in L.A. said I was too country for rock, and Sony in Nashville said I was too rock for country. This is before alternative-country, alternative-rock, Americana, all that stuff. None of that had happened yet. I fell in the cracks. It took this European punk label, Rough Trade Records; they weren’t worried about marketing like the American labels were.

I never got bitter. There’s no place for bitterness. That’s a waste of energy. I always figure, okay, if it’s not going to happen now, it’s going to happen at a certain point. I always had this thing that was pushing me and driving me, and I don’t know what that thing was. People ask all the time, “Do you feel bitter because you didn’t make it sooner?”—and the answer is always no. When I was in my twenties, I was not ready. Happy Woman Blues [Williams’ first album to feature original material], I was getting a taste of being a songwriter. Although there’s songs off Happy Woman Blues that people still want me to play; there’s a certain innocence in all of it. I guess I’m saying is the older I get, the better I get. I identify more with the jazz world and the blues world and the poetry world. My dad once said to me, “In the poetry world, nobody’s even considered until they get into their fifties and sixties.”

All the classic poets were older. There are very few younger famous poets, or younger famous writers for that matter. Kerouac was kind of younger. A lot of the jazz artists didn’t look perfect. They weren’t beautiful. The rock world, on the other hand, is youth obsessed. The blues world, nobody worries about the age thing. Look at Honeyboy Edwards. Tom and I went to see him at Cozy’s in Sherman Oaks. I was sitting there at the table going, This is a living link to Robert Johnson. The guy was unbelievable, like a young rock guy. When was the last time you saw a fucking rock musician playing at the age of, what, he was ninety-what? It blows my fucking mind.

He does two long sets, takes a break. I go up to the bar and introduce myself. He’s drinking a big glass of beer and a shot of whiskey. He’s got these incredibly beautiful hands. And I said something like, “Are you married or….”

And he goes, “I’ve got a girlfriend. She’s forty-five.”

“Really?”

“Yep. And you know what?”

“What?”

“She treats me just like a baby child.”

To him, forty-five is young. So that’s what he was saying: “I got a younger woman and she treats me like a baby child.” I’ll never forget that. He was fucking sexy. I’m serious. This guy was hot. He’s like ninety-something years old and, you know, sowin’ his oats! And I went back and told Tom and I never forgot that. That was something I wrote down in my notebook. I’ve been trying to fit it in a song ever since.

My mind’s always going, just like my dad’s was. He had these index cards in his pocket and would write something down, then put it back in his pocket. I can remember him mumbling to himself, and I do that. When Tom and I go out and I think of something, I grab a napkin. I should probably put out a book called Cocktail Napkin because I have all these napkins with lines of things, something somebody will say or I think about. And when I feel compelled, I sit down and get all those notes out.

I don’t work at it every day. I’m not really disciplined, but I’m definitely not lacking in inspiration. To me, that’s the secret. It’s not about the discipline of getting up every day and writing, it’s about staying inspired. When I feel like it, I feel like it, and work. It’s not a mathematical thing. If I knew how to explain it then I probably wouldn’t be the artist I am. I don’t mean to sound flippant. I think a lot of it, maybe, is having listened to all the right people when I was growing up. Like Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn and Ray Charles and Bob Dylan and all his wonderful melodies, like “Ramona.”

That song, you know: “Ramona, come closer, shut softly your watery eyes.” That to me is one of the greatest lines. “Shut softly your watery eyes.” Not just shut your eyes, but shut softly your watery eyes. And that melody. What about Leonard Cohen and “Suzanne”? And Nick Drake. The Doors. “Come on, baby, light my fire.” It doesn’t even have to be a complicated line. It could just be the right melody sung in the right way.

It’s only been in the last couple of years that I’ve been able to branch out and take on different characters, like writing a short story. “Memphis Pearl,” that song, I wrote about this woman I saw digging through a garbage can, and I kind of imagined who she might have been. Writing about myself came naturally to me. My fans are concerned because my songs are so autobiographical that when Tom and I got engaged—I’m serious—I did interviews and they would ask, “What are you going to write about now? You’re not searching for Mr. Right anymore. Now you’re in a relationship and you’re happy.” Well, here’s the thing about misery. I had a lot of misery when I was growing up. I have enough misery to last me for the rest of my lifetime. The misery is like a well, and I just dig into the thing and pull it out anytime I want. I have misery and then some. I don’t need to create any more. I can write about other stuff, other stories, other peoples’ lives. A lot of the songs on Blessed are like that, like “Born to Be Loved”: They’re not necessarily about me, even though everything I write has some of me in it. The hardest thing is not looking like you’re pointing the finger and blaming someone, like, “You fuck-up, you piece-of-shit fucking drunk fuck-up!” Not making it sound like that. Being empathetic but also pointing out a flaw in the character at the same time. “Lake Charles” was like that, about a guy, Woodward, who was basically a total fuck-up. He was a beautiful person—soulful and all the rest, but doomed.

This involves my dad, and it’s a true story. When I was about four years old I had befriended this little caterpillar in the backyard. I went to bed and woke up in the middle of the night to go see about it. My dad heard me get up and followed me outside. The caterpillar had died. I was quite distraught, and my dad tried to console me, so he wrote this poem called “The Caterpillar”:

Today on the lip of a bowl in the backyard

we watched a caterpillar caught in the circle

of his larval assumptions

My daughter counted

half a dozen times he went around

before rolling back and laughing

I’m a caterpillar, look

she left him

measuring out his slow green way to some place

there must have been a picture of inside him

After supper

coming from putting the car up

we stopped to look

figured he crossed the yard

once every hour

and left him

when we went to bed

wrinkling no closer to my landlord’s leaves

than when he somehow fell to his private circle

Later I followed

bare feet and door clicks of my daughter

to the yard the bowl

a milk-white moonlight eye

in the black grass

It died

I said Honey they don’t live very long

In bed again

re-covered and re-kissed

she locked her arms and mumbling love to mine

until turning she slipped

into the deep bone-bottomed dish

of sleep

Stumbling drunk around the rim

I hold

the words she said to me across the dark

I think he thought he was going

in a straight line

That should explain to you why and how I became a writer, because my dad always credited me with that line. He has Alzheimer’s now, and he told me he couldn’t write anymore. It just crushed me, because that was my whole connection with him. We were sitting in the sunroom drinking wine, and very matter-of-factly he goes, “I can’t write poetry anymore.” I said, “What?” He goes, “I can’t write poetry anymore.” Can you imagine? It was like somebody said “I can’t walk anymore” or “I can’t talk anymore.” And I just sobbed and sobbed. I still can’t believe he said that. That’s the worst thing I’ve ever heard, since I was fucking born. I love my dad so much.

Final note from Dan:

Miller Williams died in 2015. If you haven’t encountered his work, you should pick up a copy of his collected poems, and you can start by sampling some via the Poetry Foundation.

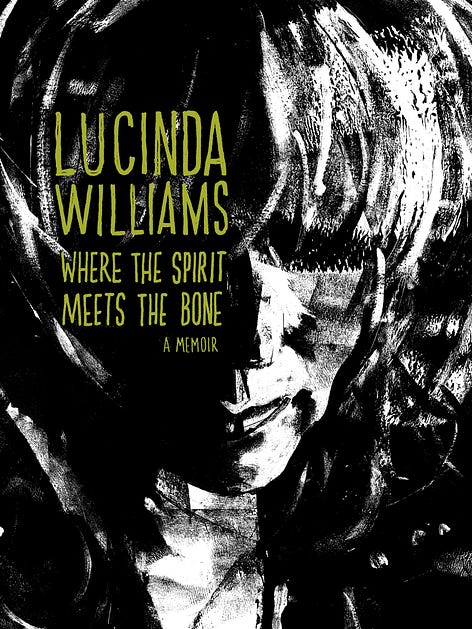

We used a line from one of his poems as the title for this Radio Silence piece (and then, incidentally, Lucinda used it for the name of the album she’d been working on in the studio on the day we visited, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone).

At times when I’m present enough in my life to practice mediation, I always finish a session by whispering this short poem to myself, a reminder of the sort of person I want to be as I step out into the world:

Compassion

by Miller Willams

Have compassion for everyone you meet

even if they don’t want it. What seems conceit,

bad manners, or cynicism is always a sign

of things no ears have heard, no eyes have seen.

You do not know what wars are going on

down there where the spirit meets the bone.

Lucinda set her dad’s poem as a song for that same record:

You had me at Lucinda, this memoir is similar to her song writing... simple, not cluttered and she allows you to feel the emotion.

This piece provides insight into her foundation; invoking Nick Drake took me by surprise but it shouldn’t have...

I have never been able to fit Lucinda into a genre and this piece, on her father, fills gaps.

Before I read this, I hadn’t thought about Poets having a family, teaching their children lessons (heck, I never dreamed of them having a child), changing spark plugs or watching TV.

Lucinda has always surrounded herself with great musicians, producers, et al yet those people were not always the famous names. To me she put emphasis on feel and friendship which is one of the reinforced takeaways I have reading this.

Nice work.

Fantastic. Thank you...