My kids, at 6 and 8, haven’t truly experienced death yet. For that I'm grateful. Our cat died two springs ago, and the kids loved her in a way, but she had already existed for them as a sort of phantom, never letting them get too close. One moment she was napping in an adjoining room, and the next she was napping underground in the backyard. Her departure didn’t register for them as a major catastrophe; it was more of a curiosity. On the morning we buried her, I saw how closely they studied my wife’s and my sadness, trying to emulate and make sense of it.

I learned something important from each death of my own childhood. In navigating those events, I began to understand the hidden depths of the people around me. Each death allowed me to witness, if not fully comprehend, the grief of others, my own grief, illness and how it can change a person, what a dead body looks and feels like, how to say goodbye to someone you love, as they lay in their final moments, how to cope with sudden, unexpected loss. In many ways I was incredibly fortunate: I didn’t lose a parent or sibling, I didn’t encounter war or famine or disaster during my formative years, but still death was all around me.

Yet none of this made me worry that I myself would ever die. The illusion of immortality, that feeling of being unconquerable, is one of the most magical things about being young. I remained certain that death was something that happened to other people.

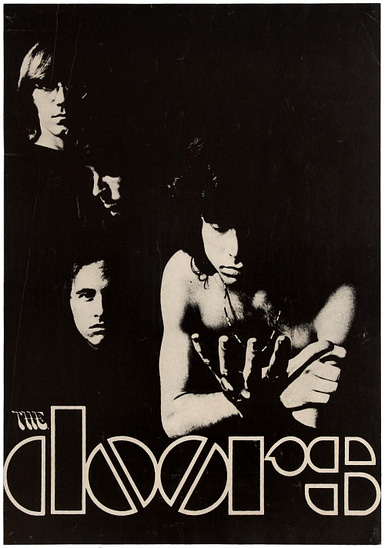

My early teenage years were marked by an obsession with the Doors. My first heartbreak, around that time, produced a stack of notebooks scrawled with dark teenage poetry, Morrison-esque in the extreme. If I could stand to peek at those pages now (I can’t), they would reveal what appeared to be an infatuation with death—reptiles, skulls, car crashes, candles, and all the other overworked metaphors.

I started collecting Dia de los Muertos art around that time. I read the Tibetan Book of the Dead, debating with friends about religion and the concept of afterlife. Death became a central component of my identity.

Part of this was posturing—I likely thought it added a sheen of mystique to my persona, however forced and calculated. Another part of it was trying to manufacture a kind of comfort over the recurring mystery of friends and relatives exiting the world. And finally, I probably was pretending that I’d come to terms with my own mortality and was cool with it. The Grim Reaper was my homey. And yet I awoke each day feeling invincible.

As I got deeper into music and broadened my altar of worship to include more rock stars who had flashed out in their primes, as I read their biographies and memorized their lyrics and wore their t-shirts—even then, 27 years old seemed like a lifetime away.

That all changed in high school when a close friend’s little brother died in a freak accident. I’ll call him Tommy. He was part of our coterie, only a couple years younger, a beautiful kid, funny and smart and kind, seemingly always there with us, and quite suddenly he was dead.

Of the deaths of my childhood, this was the most difficult to make sense of. Tommy wasn’t sick; he wasn’t bad; all in all, he’d lived a charmed life. He was younger than us. It was the first moment that I truly grasped that death was not, on an individual level, about order or justice or reason. Death was a falling leaf that might land anywhere, an expression of the chaos of the natural world. Any one of us could be struck down, in an instant.

At least, in my selfish adolescence, that’s how Tommy’s death touched me. For his family, of course, the event devastated them in a way that I won’t try to describe, since it wasn’t and isn’t mine. I can only imagine—now that I’m a father, worrying through the nights while my kids sleep upstairs—the horror of such a loss.

On the day of Tommy’s funeral, once the service concluded, I filed out of the church with my sisters and parents. We were close with the bereaved, so we turned to attend to the other solemn ceremonies of the day.

I don’t recall if I saw them myself, but five of my friends packed into a Nissan and pulled out of the church parking lot, music blaring from the open windows. I learned later that they drove around all that afternoon and evening, smoking cigarettes and blasting “Alive” by Pearl Jam on repeat. This upset me for years, though I never said anything to them about it. It seemed the ultimate disrespect to the deceased and to the mourners, to play this anthem to life on a day meant to honor the death of another kid, a friend of ours. It felt, at the time, almost like bragging.

But of course that’s not what it was. I finally came to recognize something that’s so obvious to me now: that “Alive” was their way of coping with the terrible epiphany that they were not immortal.

And I’d bet that Nissan is exactly where Tommy would’ve wanted to be. Not in a suit and tie in the sad, tragic rooms of hors d’oeuvres and tissues, but more than anything he would have wanted to be in that car, speeding along country roads with all four windows down, going nowhere in particular, shouldered in among a pack of friends lighting each cigarette off the last, singing until their voices were raw and their faces windburned and the cassette tape started to distort and the gas-tank light blinked in warning. They were alive for the moment. They were the lucky ones. And they weren’t gonna squander it.

Is something wrong, she said

Well of course there is

You're still alive, she said

Oh, and do I deserve to be

Is that the question

And if so… if so… who answers… who answers…

I, I'm still alive

Hey I, I'm still alive

Death is something I am quite acquainted with, and I believe I probably view it a little differently than most people. I’ll save those thoughts for another time.

When our daughter died just short of her 9th birthday, it was an end to her suffering, but for my wife and four living children, life would never be the same. I made so many mistakes with the other kids during that time. I allowed myself to be influenced by the masculine concept of being “strong for my family.” So, I did not allow them to see their sister’s body. I would not have them remember her lifeless form wrapped in plastic and string. I had to “protect” them.

I did far more damage than protecting in those actions. I have no idea what I thought I was keeping them safe from? Instead, I blocked their ability to process what had happened.

They suffered a loss too, and that experience was denied them by their father.

We would pay the price for that later. The eventual loss family pets (Guinea pigs) would be catastrophic. The grief and anguish went on for months upon months over a rodent when not even a tear had been shed for their sister. So severe was the trauma I had created that my special needs child (now an adult) only stopped crying for their pets fairly recently.

This grief came out the way it did because I had denied my children the closure and ability to process their loss. They didn't understand the permanence. Allow children to experience all of life… especially death. It’s the one thing we all have to face sooner or later, and while no one is ever “ready,” they can be “prepared.” Don’t think that you are doing a child any favors by delaying that experience.

Thanks for sharing this Dan. And for the Pearl Jam ♥️